|

Pioneer Christmas Trails

In

the 1840s vast lands, rich in soil and precious minerals lured hardy

men and women across barren prairies and deserts and over the rugged

mountain tops of the Western United States to a place called

California. Wagons or hand carts packed to the brim with their

belongings and supplies, they said goodbye to family and friends,

and all they had ever known for the promise of something fresh and

new.

They

also took with them their homeland memories and their traditions, to

satisfy that need to connect with something familiar. Even along the

dusty trail they would pause for a moment or two to whoop and

holler over the birth of the nation they had left behind on the

Fourth of July. Once they arrived to their various destinations

they would bring their other holidays with them as well. Christmas

was no exception.

The

majority of pioneers made it across the frontier without mishap.

However, we are more familiar with those who did not. Misguided,

misinformed, and continued disagreements, caused the great tragedies

of the Donner Party. The Donners, already behind schedule, found

themselves in the midst of an early winter. As Christmas Eve

arrived at their various High Sierra camps where they were already

half starved and frozen, the prospect of more snow just added to the

gloom. The children reminisced about Santa's visits in their cozy

homes of years past. As the snow piled deeper around them, they

realized that even Santa Claus would not be able to find them in

their peril.

|

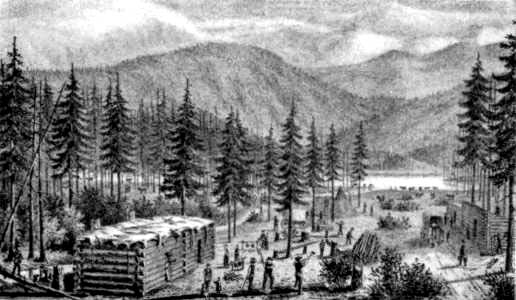

CAMP AT DONNER

LAKE, NOVEMBER, 1846-From an old drawing made from

description furnished by Wm. G. Murphy.

(From

THE EXPEDITION OF THE DONNER PARTY AND ITS TRAGIC FATE

BY ELIZA P. DONNER HOUGHTON, www.gutenberg.org/files/11146/11146-h/11146-h.htm)

|

Christmas morning for the Reed family, whose father had been

banished from the Donner Party long before, consisted of rawhide

boiled into a "pot of glue". Mother had a surprise in store for

them for dinner, however. Mrs. Reed had thought ahead when she had

purchased her last oxen and supplies from their fellow travelers who

were more fortunate than they were. Imagine the delight in the

emaciated faces of the Reed children when they found their mother

cooking pieces of frozen ox meat, tripe, a teacup of white beans, a

smaller amount of rice, a few dried apples, and a two inch square of

bacon. The children were warned "eat slowly, there is plenty for

all."

A

few years after the Donners met their fate, a group of 49ers found

themselves traveling across the Valley of Death for the holidays.

Juliet Brier remembered Christmas in the Furnace Creek Wash: "The

men killed an ox for our Christmas, but its flesh was more like

poisonous slime than meat. There was not a particle of fat on the

bones, but we boiled the hide and hooves for what nutrient they

might contain. We also cooked and ate the little blood there was in

the carcass. I had one small biscuit, but we had plenty of coffee,

and I think it was that which kept us alive."

In

And Around The Mining Camps

For

those more fortunate than the Donner and Death Valley parties,

Christmas was a lonesome prospect in the mining camps. Many miners

spent the day homesick for those they had left back East. December

25 was just another day of mining drudgery. Some banded together

for holiday revelry. A $20 dollar bottle of whisky, a $2 pound of

flour, fresh dollar a pound beef, $2 salt fish, and a one pound can

of oysters traded for an ounce of gold, provided the meal for a

group of Mokelumne miners their first holiday. Others in the gold

country typically feasted upon bear, venison, bacon, dried fruits,

and wine.

The

Sharmann family spent the Christmas of 1849 on their lonely gold

claim in their canvas structure.

With

the parents ill with scurvy, Hermann Sharmann and his brother rode

horseback 90 miles to the town of Marysville. Their hard earned $10

in gold dust supplied the family with the makings of a holiday

feast. The boys returned home with a branch of pine tree, and began

preparing flapjacks, biscuits, canned peaches. Mr. and Mrs.

Sharmann proved too sick to enjoy their sons' edible gifts, so the

boys enjoyed the meal themselves. It was a sad celebration on the

banks of the Upper Feather River.

In

San Francisco and other more established towns of the early mining

days, drunkenness, gambling, and pranks abounded. In Rich Bar,

Louise Clappe, also known as Dame Shirley wrote of oysters,

champagne, brandy and music to dance to for several days. The diary

of Alfred T. Jackson, published by Chauncey I. Canfield, notes the

Christmas turkeys promised by a local hotel in Selby Flat. For

weeks the hotel owner bragged that he would provide all guests the

luxury of a real turkey dinner. Dozens of birds were ordered from

Marysville. Those miners who knew about them took bets from others

whether the turkeys would actual appear or not. A week before the

holiday, the birds arrived, but the stakeholders decided to pay up

when they would actually be served.

The

hotel advertised the Christmas feast for $2.50 a person, and

continued to fatten up the turkeys. Two days before Christmas,

however, the turkeys disappeared. A deputy sheriff was asked to

search various miners' abodes with no luck in finding the precious

turkeys. The hotel served its meager dinner minus the turkeys,

minus dance and celebration, and only a lone mince pie to liven

things. Fifty unsatisfied customers of the hotel bombarded the

local Saleratus Ranch, expecting to find the good old boys there

dining on their turkeys, but found them enjoying old pork, beans,

and boiled beef. At last Alfred Jackson went to another miner's

cabin and found all who had placed bets that there would be no

turkey for the hotel were actually enjoying the birds for their

private dinner.

The

entire population of the mining camp of Auburn most likely spent

Christmas, 1850, witnessing the lynching of an Englishman named

Sharp who had shot and killed another miner. So outraged by the

incident, a mob seized Sharp from the sheriff, held their own court,

then proceed to hang him on an oak tree located in the middle of

town.

Three years later, the citizens of Downieville sat in court on the

day after their holiday, waiting for the sentencing of Ida Vanard,

who was being charged with murder. The court room, anxious after

the hanging of a woman three years before, broke out in applause

when the judge declared Ida not guilty of the crime.

A

young man from Pilot Hill grabbed his rifle to kill a deer on

Christmas day of 1850 only to be murdered by Indians who walked away

with his gun afterwards. When he did not return after some length

of time a party was sent out and came back with the Indian chief and

five others the following day. The young man's body was found under

a pile of leaves and sticks, his head severely beaten, and three

gunshot wounds. The Indians were immediately put to a speedy trial,

and sentenced to execution.

The Christmas Gift Mines

A

few miners wrote in diaries and letters about sending gold nuggets

home to their families as gifts. Others wrote of a particularly

good day in the diggings, then spending their find on more mining

supplies. Some mines were actually discovered on Christmas Day, and

given appropriate names. In December of 1860, a group in search of

the Gunsight lode in Death Valley, camped at Wildrose Spring. Three

miles southeast, Dr. G. George and William T. Henderson found a

large silvery lode 25 feet thick, and christened the mine the

"Christmas Gift." Though assays showed mainly antimony sulphides,

there was enough silver for George and Henderson to return to the

Panamints in April 1861.

They

collected a quarter ton of ore, staked more claims, climbed and

named Telescope Peak and organized the Telescope Mining

District. The ore again proved to be more antimony than silver, but

Dr. George persevered. The combination Gold and Silver Mining

Company was formed by the end of July, with a paper capital of

$990,000 to open the Christmas Gift and adjacent claims. A few

years later, the Christmas Gift had still failed to produce

significant amounts of silver. The camp was attacked by Panamint

Indians who killed four of the miners, and burned the company

cabin. The Christmas Gift remained closed for over a decade.

During

World War I, Frank C. Kennedy who had re-opened the mine years

before, was finally rewarded with rising prices of antimony. Los

Angeles mining engineer, Leslie C. Mott, bought the Christmas Gift,

formed the Western Metals Company, and began pulling out about

$3,000 worth of ore a day. The Christmas Gift Mine at last lived up

to its name, its worth being declared $1-million. Outside of Death

Valley, near the town of Darwin, another Christmas Gift Mine was

owned by the New Coso Mining Company. In the year of 1875, though

costs were high, six or seven tons of bullion (equivalent to 150 -

175 bars) were smelted and produced $2,000 in silver, each

day. Reports from 1914 show the Christmas Gift shipments averaging

60 ounces to the ton in silver, 45 ounces of lead, and $2 to the ton

in gold.

Christmas in Randsburg

As

years passed and more women and children came to California.

Christmas began to resemble the holiday we know today. A letter

from Marydith Haughton of Trona was given to Dr. Lorraine Blair and

read as a part of Christmas at Rand Camp II in December 2001. The

letter written by Theresa Kane (McCarthy) talks of Christmas in

Randsburg in 1897.

By

the second week of December, Theresa and her sisters began worrying

where to hang their stockings. They did not have a fireplace, and

the greasewood bush wasn't tall enough for a tree nor strong enough

to hold all five of their stockings. By Christmas Eve, Mama

finished with her baking and turkey preparations for the big

Christmas dinner, while the children sorted their long black ribbed

stockings to find the one that would hold the most amount of candy.

Following supper and baths in a long tin tub, Mama prepared to hang

the children's stockings. A white sash rope was tied to the damper

of the stove pipe of the living room heater. The other end was

fastened to the end of a large knob of Mamas high backed rocker.

The children hung their stockings on the line with wooden clothes

pins, their names attached to each one with slips of paper held on

by safety pins, then they were sent to bed for the night. Papa woke

them the next morning singing, " A Merry Christmas to All of You!"

To

their delight the children found popcorn balls, peppermint candy,

nuts, oranges, and apples in their stockings. Underneath their

stockings they found individual presents - a red doll chair with a

doll in a red China silk dress for Theresa; a green dray wagon with

horses and driver for Tom; a red fire engine complete with

horses and fireman for Leo; a china head doll with a doll bed for

Sara and a rag doll and small doll buggy for Marie.

Following breakfast, Theresa dressed in her best, took her new doll

to show off to all of her friends, and admired their gifts as

well. Christmas afternoon she came home to find Mama had laid out

a complete Christmas dinner just as many of us enjoy today, complete

with stuffed turkey, mashed potatoes, creamed cauliflower, celery

sticks, home cooked cranberry sauce, olive, pickles and home baked

bread. Mince and pumpkin pies were served for dessert as well as

fruit cake.

Bibliography:

Death Valley and The Amargosa: A Land of Illusion

by Rchard

E. Lingenfelter

University

of California Press

History of the Donner Party: A Tragedy of the Sierra

by C. F. Mc

Glashan

Stanford

University Press

Ordeal by Hunger

by George

R. Stewart

Washington

Square Press

The Darwin Silver-Lead Mining District, California.

by Aldoph

Knopf

USGS

Bulletin # 580

Government

Printing Office, 1914

Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining in the California Desert

by Larry M

Vredenburgh, G.L. Shumway and R. D. Hartill

Living West

Press

Thanks to the following websites and

the authors:

Auburn

California

Eldorado County History

Nevada County Gold Online: History: Becoming

California Christmas Found Gold Rush Miners Far From their Homes by

Don Baumart

Of

Argonauts and Holly Wreaths by John Bauer

Real Riches of the Season by Susan G. Butruile

A Desert

Christmas Memory

Project

Gutenberg

|