Most recently,

I found myself in a rare winter visit to Cerro Gordo in the

twenty first century. Roger and I were helping, to watch over

the town for a few days. The roads were dry and in relatively

good condition all the way up, except for a few icy patches in

front of our little cabin up there. Temperatures dipped to

between 25 and 50 degrees, depending upon the time of day and

whether it was cloudy or sunshiny.

|

|

A

"warm" winter day in Cerro Gordo (Jan 24, 2014) with

an outside temperature of about 35 degrees. View is

looking west down Main Street. The museum is to the

right and Owens Lake and the Sierra Nevada Mountains

are in the distance. |

On one sunshiny

day, my friend Jaclynn and I took advantage of the relative

warmth and sat in the swing off the deck of the American Hotel

with a good view of the Yellow Grade and anyone coming in to

town. It had been fairly quiet so we weren’t expecting anyone in

particular to come up.

Suddenly, we

notice a truck driving through, and we waved at them to stop. An

older man and woman were in it and the man said they just wanted

to do a drive through now and see how the town was surviving,

and would be back for a visit later. Our conversation, I from

the porch of the hotel, and he from the main road down below,

was polite and friendly, and consisted of a lot of history

between the two of us. He reflected on many visits to Cerro

Gordo and surrounding areas in the old days, with his father,

and when I asked him his name he simply replied, "Skinner." I

smiled and said, “Any relation to Max Skinner?” and he said,

"yes". A few days later when I headed back home to Los Angeles,

I thought it was time to hit my books and see why the name

Skinner sounded so familiar.

According to my

resources, the Skinner story starts with Joseph V. Skinner, who

was born in 1839, the first white child born in Fort Madison,

Iowa, and the first child born to the John Skinner family,

originally of Mohawk Valley, New York. In 1859, Joseph showed an

interest in mining and went to Colorado. The Civil War broke out

and he wound up fighting Indians with a Colorado regiment,

instead. Joseph Skinner’s tales of the Battles of Sand Creek and

of Apache Canyon were retold often to his children and

grandchildren. A spot on his scalp, bald from a scar, was

testament to the arrow that grazed his temple, ear, and scalp

moments after seeing an Indian behind a log at Sand Creek.

As the Civil

War ended, Joseph returned to Iowa. There he met Marguerite Jane

Robinson and by 1867, Marguerite and Joseph were married. In

1876, they found themselves in Missouri buying and selling

cattle. Joseph had asthma, however, and doctors ordered him to a

more favorable climate. He remembered his friend, Mary Huber,

the wife the Virginia City Yellow Jack Mine superintendent, and

she told him there was work there if only he would come.

Joseph boarded

a train to Reno, Nevada, arriving in March of 1878. He spent one

winter as Virginia City's undersheriff, then hooked up with the

Barnes brothers of Bridgeport who operated a way station. He

moved to Big Meadows, as Bridgeport was called in its early

days. In addition to homesteading a ranch, he started a

freighting business hauling perishables from Carson City to

Bodie for $3.50 a pound. With the profits he made from the

freighting, he was able to buy bigger teams and wagons to haul

heavier freight.

The following

year, 1879, Joseph sent for his family to join him. Marguerite

packed up their four children ages twelve to two; Jessie, Max,

Fred, June and Bill. They travelled by train 1for two weeks,

with sleeping bunks and a stove to cook their meals along the

way. Marguerite brought large quantities of bologna, sausage and

French twist bread, which they primarily ate along the way.

Jessie would recall that she had so much bologna and French

twist bread on that trip, she couldn’t stand the thought of

eating again in her adult years.

They travelled

through wild land with large herds of buffalo, antelope and deer

that often delayed the train as they crossed the tracks. Nights

were travelled without lights on the train, since a previous

train had been attacked by Indians. When they arrived in Reno,

Joseph met them and loaded them on the Virginia and Truckee

Railroad for Carson City. From there they boarded a covered

wagon and headed south for Bridgeport with an overnight stop at

Sweetwater which was hosted at the way station run by Tom

Williams and his family.

The Skinner

family officially arrived in Bridgeport on March 11, 1880. Snow

covered the valley and it was bitter cold. The homesteaded ranch

they called their home is now known as the Hunewill Ranch.

Joseph supported the family teaming from the forest saw mills to

Bodie which was still in its boom cycle. The Bodie Railroad had

yet to be built.

|

|

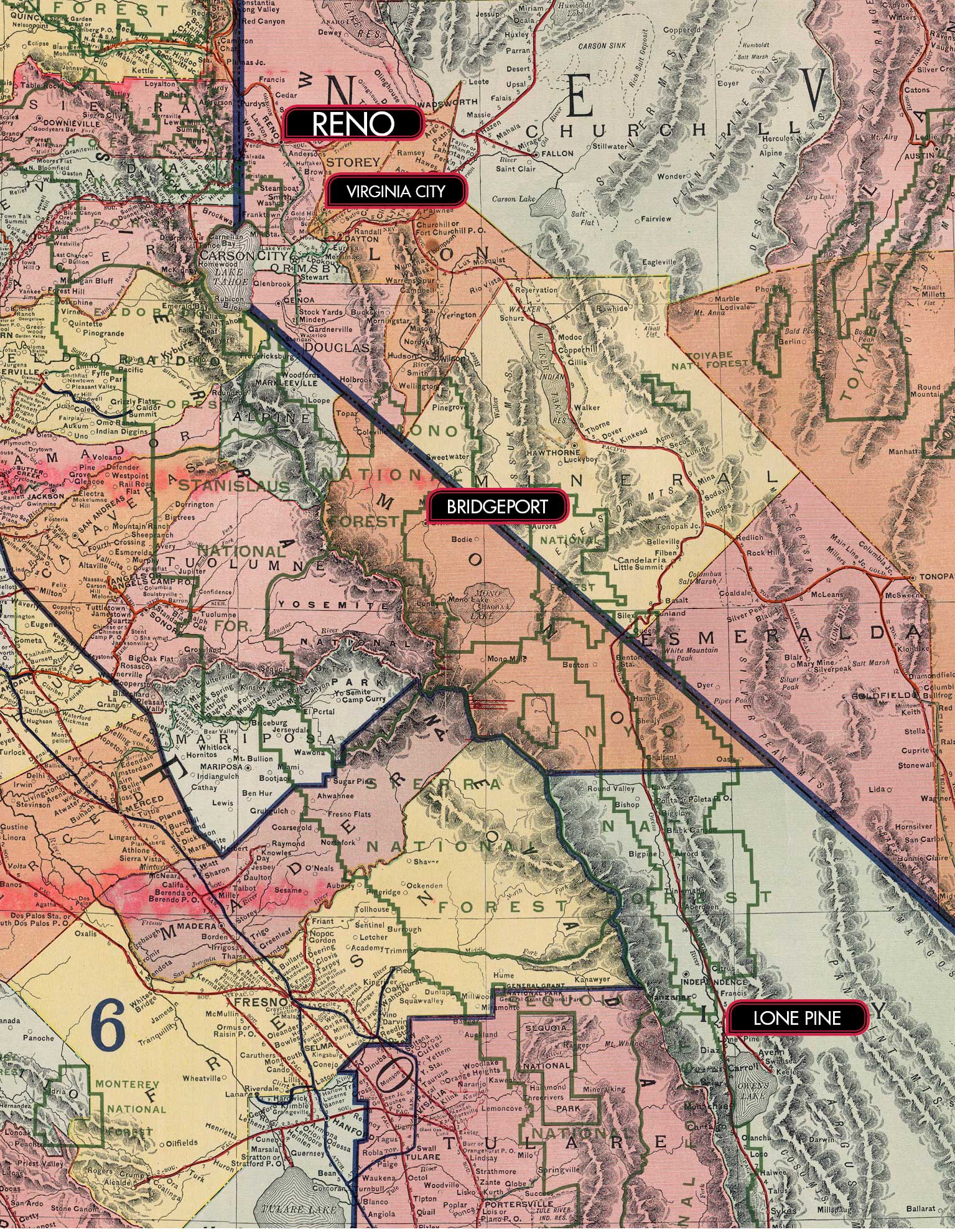

Map

showing Skinner family travels from Reno, Nevada, to

Lone Pine, Calif. Map base is 1912 Rand McNally

New County and Road Map of California and Nevada.

(Map courtesy of David Rumsey Historical Map

Collection) |

The children

attended schools in Bridgeport for one year. Joseph’s wife,

Marguerite, was often homesick for her friends and green wooded

hills. She would go out in the tall rabbit brush for a good cry

to get it out of her system, then return with a smile, because

she knew Joseph’s asthma required they remain in the West.

From the big

meadows of Bridgeport, the Skinners decided to take their team

over the Sonora Pass to Stanislaus County. Joseph teamed up with

Jimmy Barnes for a successful winter plowing wheat fields.

Barnes longed for Bridgeport, however, so by February, 1882,

they were planning the return trip.

Winter snows

required them to look for a southern passage over the Sierras.

They camped at White River until Green Horn Pass opened. At

Coyote Holes they noted barrels of water and grain left by other

travelers for return trips.

The family

arrived in Lone Pine in the Owens Valley May 10, 1882. “This is

where we are going to stay,” Marguerite announced. The family

rented the property known as the McCall Ranch and it became

their home. Another child, Lloyd, was born that same year. This

was during a period of conflicts between Indians and Mexicans.

Jessie and Max would pass by a dead Indian or Mexican along the

way to school. The ranch remained their home until 1884, when

they moved into what was known as the Castro House in Lone Pine.

Joseph relied

on his freighting skills once again, hauling from Mojave to

Bishop. On return trips he carried wheat and ore south from the

mines. He also burned charcoal in the kilns near Cartago and

hauled it to Owens Lake to be shipped to the smelter at Swansea.

He also hauled equipment to Saline Valley.

Jessie Skinner,

the eldest daughter, married Finley MacIver. They homesteaded a

ranch east of the river near the Reward Mine. Finley MacIver

became the superintendent for the Carson Company which built the

East Side Canal to irrigate ranches. Dry land became lush fields

of alfalfa and blooming orchards thanks to that irrigation. The

company attracted a colony of Quakers that settled around Owenyo.

They had no experience with irrigation or desert living.

The Quakers

sold out to the City of Los Angeles in 1905, cutting water

supplies for neighboring Skinner and MacIver ranches. In 1908,

the Skinners sold their ranch to the City of Los Angeles, and

purchased the old Lubkin place in Lone Pine. Sons, Lloyd, Bill,

and Bill’s family shared a ten acre block there. Bill eventually

owned the place until he also sold to the City of Los Angeles

around 1932. A portion of the property was given to Max Skinner

and was owned by his widow after he died. Joseph Skinner died in

Lone Pine in 1922, Marguerite moved to Eugene, Oregon, with son

Bill and his family, and lived there until 1933. Both Joseph

and Marguerite are buried in the Independence cemetery.

The Skinner

children all did well for themselves, but it was Max Skinner who

took up freighting like his father. He hauled freight from

Darwin and Owens Valley to Mojave. In Mojave he met a Harvey

girl by the name of Harriet Wilbert, and married her. He owned

the Skinner Store in Lone pine where La Florista is. Max had

hopes of going to West Point, and passed the examination.

Unfortunately as he rode from Lone Pine to Mojave by mule

infection set in his ear, which disqualified him for

appointment, so he took work on the Los Angeles Aqueduct. He

owned his general merchandise store for many years, then sold it

to become an insurance agent and justice of peace.

So I leave our

readers with these tidbits for now and the promise of more tales

from Max Skinner himself, next month.

Thanks to Paul

Skinner, for sending us on the research trail after our chance

visit up at Cerro Gordo and thanks to Paul for sending us a

picture of this treasure from his own family files.

|

|

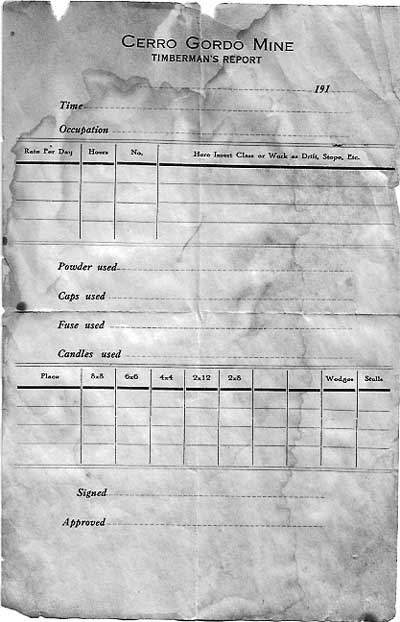

Cerro

Gordo Mine Timberman's Report (early 20th

Century).

(Courtesy Paul Skinner Collection) |

Bibliography

The Album Times & Tales of Inyo-Mono, Vol. V No.4.

Chalfant Press, Inc.

October, 1992

A Skinner Family Record by

Frances V. McIver & Pat Boyer

Conversation with Paul Skinner at Cerro

Gordo (January, 2014)

David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

(http://www.davidrumsey.com/)