This month we again

feature author/historian Robert C. Likes, and an article he

wrote for Desert Magazine in October, 1970.

Bob is also the author of

From This Mountain—Cerro Gordo, and at least four other

Desert Magazine articles. In past issues of EHC we have

featured his stories on Mono Mills, and Panamint City.

Through the magic of the

internet, Bob stumbled across our website and has become a good

friend, and mentor. He has been a source of constant

encouragement and source of information about many of our

favorite places, and just a delight to know!

Bob is currently in rehab

after suffering a stroke. The Likes family and close friends

encourage everyone to send good wishes and a line or two about

how important his works have been to desert rats and ghost

towners in the new millennium.

Even if you don’t know of

him or his works, he and his buddies at Rocketdyne who formed

the Ghost Town Club were the forerunners to modern day 4x4’ing,

and backcountry exploring, and we can thank them for paving the

way and preserving histories for us!

Please feel free to e-mail

Bob at:

The Southern

Emigrant Trail - later called The Butterfield Overland Stage Route -

stretched from St. Louis, Missouri to San Francisco. Probably the

deadliest section of the trail was through the desert areas of

Southern California.

GREAT

TROUGH in the Anza-Borrego desert area of San Diego County winds

through the desolate Carrizo and Vallecito Valleys and then rises

into the cool, green costal hills of southern California. This

natural passageway is the legendary Carrizo Corridor.

Along

its course of rutted and sandy washes flowed a steady stream of

California history, for this was the last leg in the journey along

the southern Emigrant Trail and the colorful butter field overland

Stage Route.

Kit

Carson passed this way in 1846, guiding General Stephen Watts Kearny

and his dragoons through the corridor when it was nothing more than

a wilderness between waterholes. One year later, Colonel St George

Cooke and his Mormon Battalion followed Kearny’s route and

established the first wagon road into Southern California. This

wagon road became known as Cookes Road, or Sonora Road, until the

discovery of gold brought a flood of Americans westward in 1849.

From this date on, it was called the southern Emigrant Trail.

In 1850,

great herds of sheep and cattle were driven across the old trail to

feed the exploding population on the west coast. Because thousands

of animals perished and left a trail of bleaching bones from Yuma to

the Carrizo Corridor, the southern Emigrant Trail was called the

Jornada del Muerto - Journey of Death.

By 1856, the

United States Government realized it had a growing communication

problem with this far-flung empire on the Pacific coast. A mail

contract linking San Antonio with San Diego was awarded in 1857. The

first mail crossing the Colorado Desert and through the Carrizo

Corridor on mule back was known as the “jackass Mail.”

A second and

larger contract was awarded to John Butterfield in 1858. The first

mail pouches were loaded aboard the departing Butterfield Stage in

St. Louis, Missouri, and in exactly 23 days, 23 hours and 30

minutes, the mail pouches were safely delivered in San Francisco,

California, more than 2800 miles away.

|

|

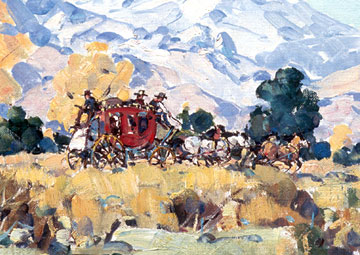

The

Butterfield Stage makes its way to California. |

Exploring the

Butterfield Overland Trail from the vanished Carrizo springs Station

to the old Warner Adobe reveals the least spoiled section of its

entire route in California.

Although this

section was the gateway to the promised land, it is doubtful that

the traveler looked forward to making the passage. With its annual

rainfall of something less than five inches, this lonely land

supports only an arid growth of ocotillo, cholla and indigo brush,

though there are stands of smoke trees and mesquite in the washes.

In 1847, Colonel Cooke described the eroded hills and rocky slopes

as “…the worst 15 miles of road since we left the Rio Grande.” When

the Overland Stage established a route through the corridor, it was

the epic battle of man against the elements, with a succession of

Indian raids, holdups and accidents, thrown in just to make it

interesting.

The Carrizo

Gap, through which the Carrizo Wash passes, is the eastern entrance

to the Carrizo Corridor. Following this route, the butter field

Overland Stage located the first way-station at Carrizo Springs.

This section of the old trail crosses a navy bombing range and

special permission is required before entry. The stage station at

Carrizo Springs has completely vanished.

After leaving

Carrizo Springs the old stage road followed the Carrizo Wash east

until it reached the junction of the Vallecito Wash. Turning up the

Vallecito Wash, the trail plowed through the sand to a point nine

miles from the Carrizo station where it left the wash to reach Palm

spring, a short distance away. The first native palms,

Washingtonia filifera, seen in California by a non-Indian were

the ones at Palm Spring. Pedro Fages first described the palms in

1772. Sixty-five years later Colonel Cooke reported a clump of 20 to

30 palms at the spring, but by 1853, after a steady stream of gold

seekers, the number of palms had dropped to three or four.

When the

Butterfield line built an animal changing station at the spring in

1858, the majestic grove of palms had been reduced to a few burnt

stumps. Today the site of the Palm Spring station is marked by a

monument standing in a clump of green mesquite, and three small

palms. The spring still provides water at this small oasis, and the

serenity is in marked contrast to the flurry of activity that took

place when this was a vital oasis along the Butterfield Trail.

After leaving

Palm Spring, the old road continued following the shifting sands of

the Vallecito Wash until it reached one of the most famous way

stations along the route. Vallecito was the first oasis with an

abundance of water and green grass, providing welcome relief for the

weary passengers after days of exposure to the hat and glare of the

desert.

W. L. Ormsby,

a passenger in 1858, commented, “….a perfect oasis,” then went on to

say, “ …a most refreshing relief from the sandy sameness of the

desert.” The Vallecito station was originally constructed of

sod-bricks with a roof of hand-hewn beams, pegged and tied in place

with rawhide, then covered with willow poles and tulles before a

final topping of sod. The famous station was reconstructed in 1934,

and today it is a San Diego County Park.

Many colorful

stories centered around the Vallecito stage station. One such

account was the night “Ol’ Bill,” one of the drivers, was held up a

few miles south of the station. Five men on horseback engaged in a

running gun battle with the passengers on the stage as Ol” Bill had

his team going “hell-bent-for-leather.” Just when it looked as

though the stage might reach the safety of the Vallecito station,

one of the animals on the team was shot and the stage came to a

terrifying halt.

Using the

coach for cover, “Ol’ Bill and his armed passengers continued to

hold of the bandits, forcing them to retreat. After another volley

of gunfire, the bandits rode off into the night. Soldiers who had

been stationed at Vallecito and who had heard the shooting, came

riding up just as Bill was cutting the dead animal out of the

harness. After a brief exchange of words, the soldiers rode off in

pursuit of the outlaws and bill headed the stage toward Vallecito,

feeling sure the bandits would be caught.

The next

morning, Ol’ Bill was astonished to see there were no prisoners.

When questioned about this, the corporal in charge of the detail of

soldiers smiled, then replied, “Well, let’s look at it this way,

bill. Vallecito has no accommodations for prisoners - outside of the

graveyard, that is.”

From

Vallecito, the road went west, gradually gaining elevation until it

reached the upper end of Vallecito Valley, where it turned and

entered a narrow canyon. This was the only passageway between

Vallecito and San Felipe Valleys, and it was here that Colonel Cooke

and his men were almost defeated in their attempt to blaze a wagon

road into Southern California.

“I came to the

canyon and found it much worse than I had been led to expect,” Cooke

later reported, “…there are many rocks to surmount, but the worst is

the narrow pass.” All of their road building tools had been lost

when the party forged the Gila River in Arizona, so axes were used

to increase the opening. Even then, the chasm was too narrow by a

foot of solid rock, and Cooke ordered the wagons to be taken apart

and carried through. It required two days for the men to work their

way out of the canyon. The pass was widened for the Butterfield run,

and was known as Cookes Pass or Devils Canyon.

For some

unexplainable reason, the pass now bears the name of Box Canyon, and

for obvious reasons, it is by-passed by the paved highway. There is

a historical marker here, and a parking area from which you can look

down into this famous pass. However, a far more rewarding experience

is to climb down into the narrow defile and view it from the same

perspective that confronted Cooke in 1847.

Box Canyon was

the end of the Carrizo Corridor and the old stage route became

easier as the team of horses followed the rutted ribbon into more

open country. After crossing a dry lake bed, the trail led straight

up a rocky ridge with a grade so steep passengers had to get out and

either walk up or push the coaches up the incline. Because of this,

the ridge became known as Foot and Walker Grade. Upon reaching the

summit, the course ahead became routine and allowed the coach and

exhausted passengers to move swiftly through the lower reaches of

the San Felipe Valley. The next stop was the San Felipe Station. The

site is located on private property just north and a little west of

Scissors Crossing.

The next 16

miles of the pioneer trail continued north through the increasingly

fertile San Felipe Valley and crossed another pass before it dropped

down between the rolling hills surrounding the station at Warner’s.

The historical

marker at the old Wilson Store proclaims it to be the butter field

Overland stage station, yet according to historian William Wright,

this structure had not yet been built when the Butterfield Stage

discontinued operations in 1861. Wright claims the Wilson Store was

one of the two buildings constructed in 1863 at a spot known as

Kimbleville. He acknowledges the Wilson store was later used as a

stage stop, but not for the Butterfield line. Instead Wright says

the old Warner adobe, built in 1849, is the real Butterfield stage

station. The Warner adobe is located one and a half miles north of

Wilson’s store, and equidistant between the San Felipe Station to

the south, and the Oak grove Station to the north. However, both the

Wilson store and the Werner adobe are historic landmarks, and worth

the time to visit.

|

|

Old

Stagecoach Trail, by Margorie Reed, 1958.

Original painting at the Wells Fargo History Museum

Old Town San Diego, California. |

At Warner’s

the trail branched, one heading southwest to San Diego by way of

Santa Ysabel; the other pressed on in a northwest direction across

the small valley and through the hills until it reached the Oak

Grove Station ten miles away. The store at Oak Grove utilized the

foundation and ancient walls of the original Butterfield Station.

From here the stage route generally followed what is now State 70

until it reached Temecula, with a stop between at Aguanga.

With the

termination of the Butterfield Overland route in 1861, the decline

of the Southern Emigrant Trail began. More northerly routes were

being discovered and used, particularly the Cajon and San Gorgonio

passes. New routes were being used from San Diego to Yuma via Camp

and Jacumaba, and even the discovery of gold in the mountains west

of the old trail in 1870 did little to revive its use.

In the early

1900s, the pioneer trail through the Carrizo Corridor lay almost

forgotten. It was simply a road that “began nowhere, and ended

nowhere” - a sad epitaph compared to the address Colonel Cooke gave

his men upon completion of their assigned task.

“History may

search in vain for an equal march of infantry,” he said. “We have

dug deep wells which the future traveler will enjoy…..we have worked

our way over mountains….. hewed a passage through a chasm of living

rock more narrow than our wagons…and thus marching half naked and

half fed, and living upon wild animals, we have discovered and made

a road of great value to our country.”

Much of this

famous route lies within the boundaries of the Anza-Borrego Desert

State Park, and so the areas of historic interest are preserved for

present and future generations to see and appreciate.

Read

More about the Butterfield Stage

Adventure No. 12 Anza-Borrego State

Park:

http://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=638

Vallecito Station

http://www.aroundandaboutsandiego.com/vallecitostagestation.html

Phantoms Of Vallecito Station

http://www.legendsofamerica.com/CA-Vallecito.html

Life and Times Of the Vallecito

Station by Ruth MacGill

http://www.gather.com/viewArticle.jsp?articleId=281474976972513Life

|