|

Since the start of mining operations in Bodie, California,

equipment was driven either by muscle power or steam power. While

there were usually plenty of strong backs willing to work for good

wages, muscle power had its physical limitations. It was steam,

produced by the burning of wood that turned the stamp mills, raised

the ore carts and lowered the men and equipment into the mines.

|

|

| Old

boiler at Bodie. |

Wood was also burned in the residents' uninsulated homes to

provide heat and cook meals.

But wood was a precious commodity in the high country

mining town. The nearest forests were miles away in the Sierras or

south of Mono Lake. Wood had to be hauled on the backs of pack

animals, or in wagons. During the winter months, Bodie was isolated

from wood shipments by 20-foot snow drifts.

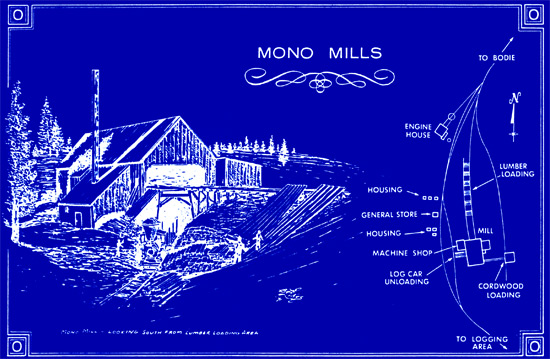

The Bodie Railway and Lumber Company was formed in 1881 to

build a rail line from Bodie 32 miles to the Jeffrey pine forest in

the volcanic hills south of Mono Lake. A lumber camp and sawmill

were built at Mono Mills. The mill and the locomotives were, of

course, powered by steam.

|

|

Drawing of Mono Mills by Robert Likes. |

The railroad operated during the snow-free months of the

year, usually closing down by November and resuming operations in

April. Bodie's fortunes began to decline, ironically, after the

railroad was completed. None the less, the little narrow gauge short

line operated intermittently until 1917. There were even grandiose

plans to connect the line to the Slim Princess (Carson and Colorado)

tracks in Benton.

Mines and mills consolidated operations or closed entirely

as ore bodies played out. Those that survived continued to be

powered by steam.

Thousands of miles away from Bodie, a battle of

technologies was raging that would eventually penetrate Bodie's

remoteness. Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse were waging a war

of words and sparks to achieve dominance in the new field of

electrical transmission.

Edison was convinced that locally generated direct current

(DC) was the power source of the future. Westinghouse, also an

accomplished inventor, realized that DC could not be practically

transmitted over long distances because of voltage drops. He was

convinced alternating current (AC), boosted (transformed) from low

voltage to high voltage for transmission, then transformed back to

low voltage at the point of use, was the solution.

Westinghouse held the U.S. rights for several transformer

designs and acquired outright the rights to Nikola Tesla's polyphase

induction motor designs. By 1890, Westinghouse was selling more than

$4 million worth of AC equipment annually.

Edison's plans for DC distribution were short circuited in

1893 when Westinghouse won the bid to power 180,000 incandescent

lights at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Back in Bodie, steam was still king. Wood was going for $10

per cord and the Standard mill

|

|

Thomas

H. Leggett |

was spending $2,000 each month to process 50 tons of ore

daily. The 24-year old superintendent, Thomas Leggett, had read

about a mine in Telluride, Colorado that had installed a

Westinghouse AC electric motor powered by hydroelectric power

generated three miles away.

While Bodie had sufficient water for its mining and

drinking needs, it lacked the volume and flow needed to generate

hydroelectric power. The nearest source was 13 miles away on Green

Creek, south of Bridgeport.

Leggett concluded

that if power could be carried for three miles, it was fairly safe

to try for 13 miles. He consulted with representatives of Edison's

General Electric Co. in San Francisco. "I found that the development

of power-transmission by electricity was in such an early stage that

they were still wedded to the direct current, and little as I knew

about electricity, I felt the uncertainty of the methods they

proposed," Leggett recalled later in an interview.

"I then consulted

W. F. C. Hasson, electrical engineer, graduate of Annapolis, who had

just opened an office in San Francisco-in fact, I had the honor of

being his first client," Leggett said. "This resulted in tying up

with the Westinghouse company, which took the contract to carry the

power for that distance-13 miles-using a 120-kw. generator at the

water-power end, direct-connected with Pelton water-wheels under

300-ft. head, without transformers, the current being generated at

3000 volts and carried on No. 1 bare copper wire, to Bodie, where it

was applied to the operation of the mill."

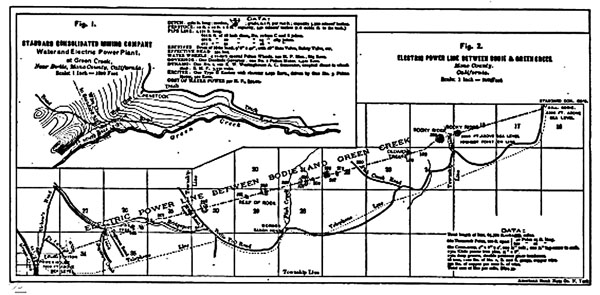

|

| The

Green Creek power house and power lines from Twelfth

Report of the State Mineralogist, 1894 by Thomas H.

Leggett. |

Construction

began in late 1892 on the Green Creek power house, 355 feet below an

old ditch that had been cleaned of debris and fitted with a penstock

and 18 inch diameter pipe. Water was delivered at 152 p.s.i. to the

21-inch Pelton wheels driving a Westinghouse generator producing

3,390-3,530 volts AC.

|

|

Diagram of electric power line from Green Creek to

Bodie. |

The boiler and

steam engine had been disconnected and the Standard mill retrofitted

for electric power in mid-1893, idling a number of workers in the

mill and mine. This did not sit well with the idled workers or the

town in general. They refereed to the project as "Leggett's folly"

and went so far as to ostracize his wife, Fanny, from social events.

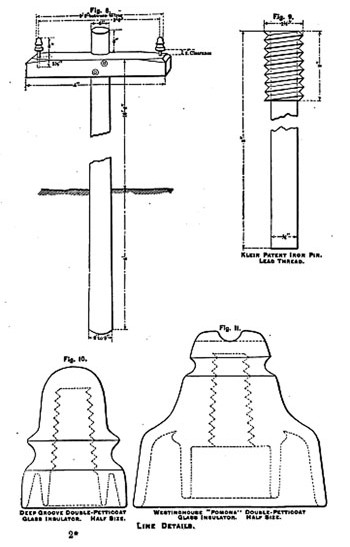

The electricity

generated at Green Creek was carried over two bare No.1 copper wires

stretched 67,760 feet from the power house to the Standard mill.

The larger diameter No.1 wire was chosen over smaller No. 6 wire

because of its increased strength. The larger wire also

eliminated the need for step-up transformers and simplified the

transmission system's design.

The two bare

wires were supported on 21 foot, 6 inch diameter poles set 4 feet in

the ground. Through town, and in areas of deep snow, 25 foot poles

were used. The poles were

|

| Pole

No. 40; 4,000 feet from mill. Wire is 17 feet above

ground at pole. Snow drift is 15 feet deep (March,

1893). The wires are bare copper and carry 3,100 volts. |

spaced 100 feet

apart and each fitted with a 4 x 6 inch cross arm. The terrain

surrounding Bodie is tough and rocky. Leggett's crew used 500 pounds

of dynamite to blast the pole holes.

|

|

Power pole and insulators. |

The wires were

attached to deep groove glass insulators. When the electricity

reached Bodie, its potential had been reduced to about 3,100 volts

due to line losses.

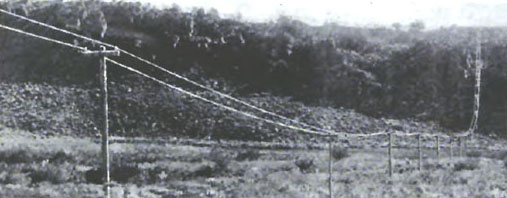

Contrary to a

popular story, the power lines were not run straight because

of fears of electricity shooting out the wires at bends. The lines

were run as straight as possible because a straight line is the

shortest distance between two points, thus maximizing the use of

copper wire. Photographs of the original lines show bends and sags

as the lines climbed over hills.

|

|

Summer view of poles 10 miles from Bodie looking west.

Notice how the wires bed is they climb the hill in the

distance. |

Telephone lines

following a different route provided the necessary communication

between the mill and power house to synchronize the generator and

motor.

The Standard mill

and offices were the only buildings on the original electrical

circuit. A 120 h.p. synchronous motor ran the twenty 750 pound stamps,

concentrators, pans, agitators, settlers and machine shop equipment. A transformer stepped

down the voltage to 100 volts for lighting the in mill building and

nearby offices. After a 30 day test period, the system was put

into full operation late in 1893.

|

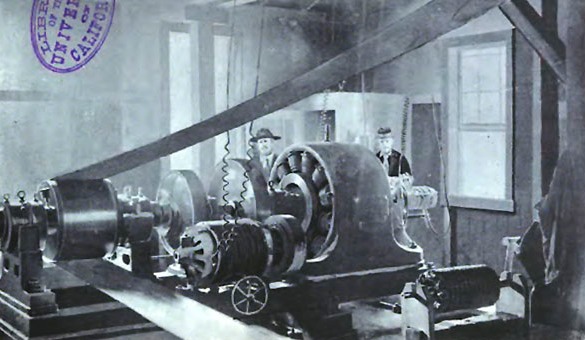

|

|

Motor room in operation at Standard mill. |

The Standard mine

atop the hill still relied on steam power to operate the hoists as

AC motors run at a constant speed and are unsuitable for such use.

After a fire in the mine's hoisting works in 1894, Leggett installed

a DC-powered hoist inside the mine and a DC generator inside the mill.

The rest of the

town, too, still burned wood for fuel, and continued to do so

for the next 17 years until December 24, 1910, when a new

hydroelectric plant at Jordan began supplying power. Unfortunately,

the power from the original Jordan plant lasted only until March 7,

1911 when the entire power plant at the base of Copper Mountain was

erased by an avalanche (see

www.explorehistoricalif.com/december07.html for the story on the

disaster).

|

|

A

Stanley Electric Mfg. Co. generator sits near the

entrance to Bodie today. |

Bibliography

Electric Power Transmission Plants and the Use of

Electricity in Mining Operations

by Thomas

Haight Leggett

Written

for the Twelfth Report of the State Mineralogist, 1894

Interviews with Mining Engineers

(interview

with Thomas H. Leggett)

by T. A.

Rickard

Mining and

Scientific Press, 1922

Christmas Delivery at Bodie Sparks Jordan Disaster

by Cecile Page Vargo

Explore Historic

California, December 2007

Developments in Electricity and Bodie’s Long Distance Power

Transmission

by

Michael H. Piatt

http://bodiehistory.com/power.htm

George Westinghouse, Thomas Edison & the Battle of

the Currents

How dead dogs and botched executions helped pave the

way to the power system we enjoy today

by Kevin Jones

http://www.barks.com/2003/03-10hist.html

|